The Wall Street Journal – which is for the most part a bastion of data-based reporting aimed at markets – has joined the ranks of fake reporting on pam oil.

Their most recent piece, Soaring Demand for Palm Oil Puts Rainforests at Risk Again, is based on the idea that higher global prices for palm oil means higher deforestation.

This is an idea that is liked by many conservationists. Why? It supports the idea that if demand for palm oil falls, deforestation will fall too. So, all the world needs to do to stop deforestation is stop using palm oil.

But things really aren’t that simple. And correlation doesn’t equal causation.

Here’s why.

Look at expansion, not just deforestation

Farmers aren’t ‘choosing to deforest’, they are choosing to plant, and this is an investment decision based on any number of factors or incentives – not just price.

It is therefore more useful to look at a correlation between prices and planted area, which is a better reflection of a planting decision based on prices.

Peaks in global vegetable oil prices took place in early 2008 and late 2011 before falling. But the local price for palm oil – the price paid to farmers — has levelled out since 2011.

By WSJ’s logic, any investment decisions taken in that time should have resulted in consistently larger planted areas for palm oil.

While there was a sharp increase in oil palm area in Indonesia from 2009-2010, Indonesian statistics indicate there was no similar increase in planted area 2012-13. This also lines up with USDA data on oil palm harvested area and CPO output.

The next sharp increase in planted area took place from 2016-2017 according to FAO data – but there was no earlier price spike. Prices were at that point relatively low.

So, we are really talking about a single correlation between global price and deforestation in 2009-10.

Do farmers expand their plantations if they get higher prices? If their balance sheet and business – and the weather — allows it.

The current situation is one of high vegetable oil prices alongside higher input costs (labour, energy, fertiliser) and rising interest rates. At the firm level, does this mean higher profit margins and a healthy balance sheet? Not necessarily.

Similarly, the planter needs to have access to land that can be planted and the right permits for planting. If these aren’t available, neither firms nor their financiers will support the expansion.

The deforestation-price link – if there is one – is just not well understood.

It can’t explain, for example, why Brazil’s forest loss was so high while soybean and beef prices remained flat in 2016-2017 and in 2000 to 2009. It remains a hypothesis, along with many others, that further underline how complex deforestation is.

Attributing it to a single commodity and its price isn’t helpful – and it won’t stop deforestation.

This is just another deforestation scare story that continues to demonise palm oil at the expense of the the poorer countries in Africa and Asia that produce it.

Western pressure didn’t stop deforestation, Indonesia did

There are many people who have invested their careers in the idea that stopping palm oil means an end to deforestation. This is why so many campaigners are reluctant to attribute Indonesia’s fall in deforestation rates to actions by the Indonesian government – instead, they claim, it was the NGOs who did it.

The WSJ article leads with this claim: “Pressure from businesses and environmental groups has slowed the destruction of rainforests to produce palm oil in Indonesia.”

This claim is based on a report from Chain Reaction Research (CRR), a US-based sustainability analytics firm, which states that 83 per cent of refining capacity in Malaysia and Indonesia would not buy palm oil linked to deforestation.

While the CRR research is admirable, it is easy to misinterpret, and Western NGOs have been attempting to take the bulk of the credit for falls in Indonesia’s deforestation rates.

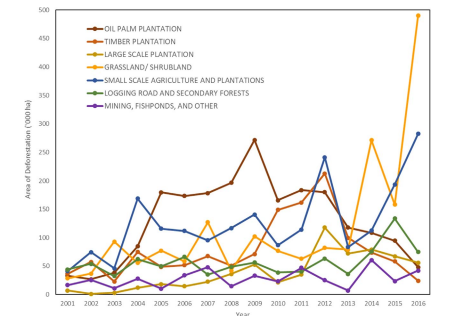

Generally, estimates have put the contribution of large oil palm plantations to Indonesia’s deforestation at around 20 per cent over the past two decades – which also squares with new research released last month.

In recent years this has fallen, with small-scale agriculture significantly overtaking other drivers of deforestation according to one analysis.

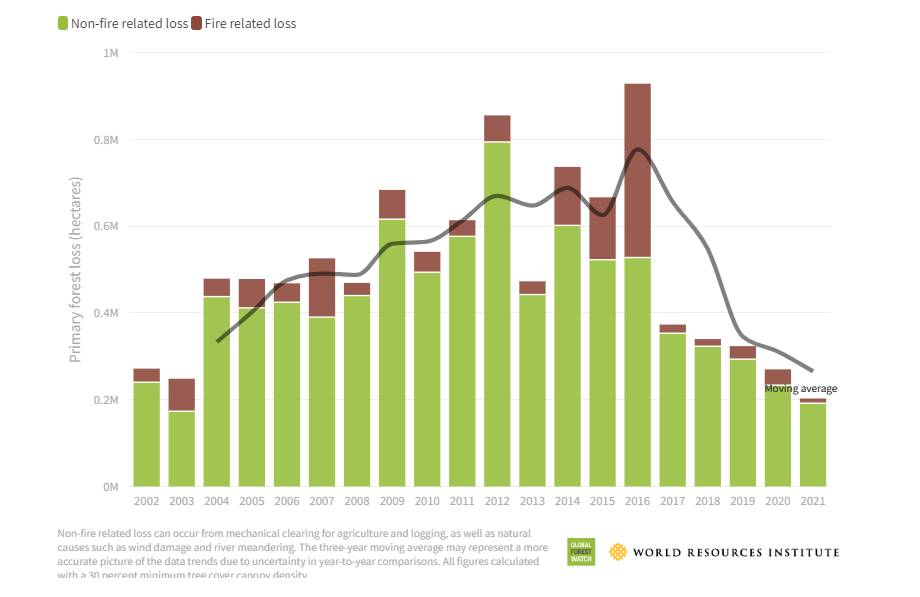

The first Indonesian forest moratorium was introduced in 2011. This applied to all deforestation activities, not just palm.

Deforestation trended down in subsequent years as the moratorium was implemented and extended. Given that all deforestation fell across the board, it stands to reason that the moratorium has been a key driver – despite the efforts of some anti-palm NGOs to claim credit.

This also makes sense for one additional – commercial – reason. If it was only Western NGO pressure that was responsible for this change, other players could enter the market, establish new plantations and refining capacity, and sell to the world accordingly. This has not happened.

There is no doubt that trader policies are preventing crude palm oil (CPO) producers from accessing some parts of the market. But there are vast swaths of the market where this simply does not apply.

Consider this: CRR states 83 per cent of refining capacity in Malaysia and Indonesia is covered by NDPE policies, but the non-NDPE refining sector in Indonesia is closer to 30 per cent.

On average, Indonesia produces around 42 million tonnes of palm oil every year. Around 7 million tonnes of crude palm oil (CPO) is exported (17%). Around 4.4 million tonnes goes to India. The remainder is refined.

This means there’s around 35 per cent of the market that isn’t covered by NDPE at any point.

Why is this important? Because the significance of NDPE policies – and NGO pressure — needs to be put into context alongside the forest moratoria that have been put in place by successive Indonesian presidents.

Washington Post actually got it right

WSJ’s oversimplification of an issue impacting the largest agricultural commodity from the largest economy in the region – without speaking to any representatives from the industry or Indonesian officials – is a new low point for a fine publication. And it’s not the first time this has happened. Consider the outcry if a similar story ran on US soybean without input from the American Soybean Association or the USDA.

Even the Washington Post has managed to highlight the real issue at play with rising vegetable oil prices – and it isn’t invented fears over deforestation. It’s real fear of food price rises – and palm oil is the key factor in preventing runaway food price inflation of vegetable oils.

WaPo – normally the subject of WSJ derision and a home for anti-palm campaigners – actually got it right. They quoted an agribusiness analyst, who stated:

“The ban [on] Indonesia[n] [palm exports] will be short-lived … They have more than they need, they don’t have enough storage and it’s worth a lot. It is driving up prices temporarily, but a rising tide lifts all ships — prices for all oils are going up.”

Indonesia and Malaysia produce and export the vegetable oil that is cheapest, most efficient, and most widely-used. The Post highlights the knock-on effects for the world’s lowest-paid. Without palm oil – including palm oil from historic deforestation – this crisis would be an order of magnitude worse.

WaPo also highlights the big picture: this crisis is global and impacts billions of people across the world. WSJ seems content pushing a niche bandwagon.