RSPO is pushing out its credentials on human rights and labour rights, but it’s apparent that the organisation has come to the party a little late as the global debate has ramped up.

As we have argued in the past, RSPO’s strong emphasis on the environment has unfortunately meant that the social aspects of certification have been neglected somewhat.

Several years ago the debate was largely about whether RSPO certification was inclusive and flexible enough to include smallholder farmers in an equitable manner.

However, that debate moved on as it became evident that national certification schemes in Indonesia and other countries would be the ones able to fill that gap.

As Western countries accelerate regulations that seek to restrict imports of palm oil and other commodities based on social or labour aspects, RSPO’s gaps are becoming clearer and more concerning for member companies that see more prominent questioning of their social – as well as environmental – bona fides.

Much of the pressure on worker rights in global supply chains has been concerned with conditions in factories, i.e. manufacturing, which is traditionally where labour activism has taken place. Indeed, for rubber products in the region much of the pressure has been on factories rather than plantations. This has, however, been changing and agriculture across the globe is coming under new scrutiny.

The question for RSPO as it moves into its 2023 Standards Review is whether it can successfully introduce and implement a more extensive system with the support of its business members.

Companies that already have social audit systems in place may see it as overkill. Social NGOs may see it as opportunity to introduce stronger codes. Anti-palm groups may see it as an opportunity to introduce something completely unworkable.

There is the additional question of whether RSPO’s initiative comes too late and the EU will rule out voluntary systems as a means of compliance with its forthcoming Due Diligence and Forced Labour regulations (this would be a reversal from the position on biofuels, where the RSPO-RED system was approved by Brussels as a certification).

RSPO will need to tread carefully.

Is Brussels trying to undermine Switzerland’s trade deals?

The EU has put itself in the firing line again on its approach to regulating palm oil imports. At a meeting earlier this year, EU trade officials were asked if it would be possible to take a similar approach to Switzerland when it comes to palm oil imports under a trade agreement with Indonesia.

Just to remind, the Swiss government’s approach on palm oil imports is simple: palm oil imported with a sustainability certification has a lower import tariff. The idea is that it gives producers and importers a clear incentive to switch to sustainable production systems that are in line with the trade and sustainable development goals in the broader EFTA-Indonesia agreement.

In response, EU officials stated:

“On the EFTA treatment of palm oil, the Commission indicated that Switzerland is importing a very limited quantity of palm oil from Indonesia, whereas the EU imports four million tons each year. Switzerland has restrictive conditions that would be impossible to implement at the scale of the trade between the EU and Indonesia.”

This is, in our opinion, nonsensical.

There are two distinct issues here: the volume of palm oil and the compliance measures required.

It’s true that Switzerland imports a relatively small amount of palm oil (around 10,000 tonnes annually versus, say, the Netherlands at 2.5 million tonnes). The same can be said for every single type of import into Switzerland, and the EU’s customs agencies are significantly larger as a result.

The fact is that there are compliance requirements on every single shipment of palm oil that goes into the EU at every single port. These requirements range from sanitary and phytosanitary requirements to taxation measures.

The Swiss approach of requiring certification to obtain a lower tariff would require an additional compliance check, it’s true. But it is completely absurd for the EU to claim this is a reason not to implement the policy. The EU is currently proposing additional compliance checks for palm oil anyway …

The deforestation regulation is going to put import declaration requirements on imports – including data around geographical location and adherence to other environmental norms – that will require additional compliance checks (as well as a mountain of other bureaucracy). Likewise the various initiatives on corporate due diligence and reporting.

In other words, Brussels is taking a path that will make it more difficult to import any palm oil at all – but is rejecting a measure that would ease some of these burdens for the most sustainable producers, incentivising change.

There is another element to this: which is a serious whiff of condescension from Brussels towards Switzerland’s trade practices. The EU is effectively saying it doesn’t trust or respect the Swiss agreement with Indonesia. It’s no secret that EFTA countries are trying to wean themselves away from dependence on the EU, and is succeeding by inking deals across the globe. This success is built, in part, on offering flexibility and genuine cooperation with their trading partners including Indonesia. The EU should actually learn something from this approach, instead of discrediting it.

Palm Bans: Careful What You Wish For

Last week we pointed out that the EU’s palm trade restrictions are likely to lead to a higher global price by pushing up prices in a major market – at the same time prices are being pushed up by Indonesia’s palm oil export ban, which was expanded (temporarily) to all palm oil including used cooking oil.

This has capped off vegetable oil shortages that have resulted in supermarket chains such as Tesco rationing sales at the consumer level.

Just to remind, palm oil makes up around 35 per cent of the global vegetable oil market; around 25 per cent is Indonesian palm oil.

Taking palm oil off the global market altogether is the dream of many anti-palm activists. But as producing countries have often underlined, this would have significant economic consequences for consumers and households around the world – and this is being borne out this month.

Despite this, the activists have not given up. A new anti-palm narrative is trying to pin the crisis on Indonesia’s biofuels policy, re-hashing the food versus fuel debate that first emerged during the global financial crisis.

There are two assumptions here. First is that Indonesian palm oil is a major feedstock for biofuels. The second is that Indonesian biofuels policy makes a significant dent in global prices.

The USDA says palm oil makes up around 35 per cent of vegetable oil production, followed by soybean oil (30 per cent) and rapeseed (14 per cent).

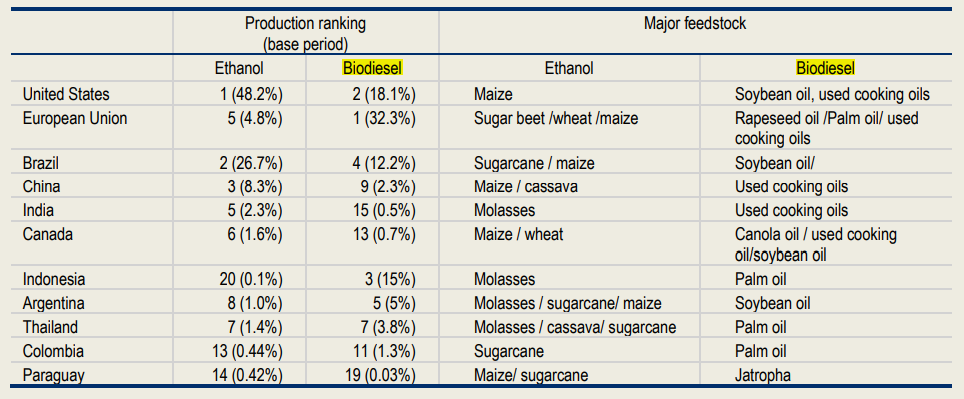

According to the OECD and FAO, 15 per cent of the world’s vegetable oil supply goes to biofuels. Around 30 per cent of the world’s biodiesel comes from palm oil; 25 per cent comes from soybean oil; and 20 per cent from rapeseed.

Parsing this, it means that around 4.5 per cent of the world’s supply of vegetable oil becomes palm-based biodiesel; and around 3.8 per cent of this becomes soy-based biodiesel; around 3 per cent becomes rapeseed-based biodiesel.

But is this surprising? Given that global palm oil production is more than double that of rapeseed, it only stands to reason that more palm would be used in biodiesel.

But here’s the rub: based on the above OECD figures around 12.8 per cent of the world’s palm oil goes to biodiesel, and around 12.6 of the world’s soybean oil goes to biodiesel. But around 20 per cent of the world’s rapeseed oil goes to biodiesel. In terms of diverting more of production to biodiesel, rapeseed is the biggest culprit.

The world’s two largest producers and consumers of biodiesel are the European Union (32 per cent) and the United States (18 per cent), followed by Indonesia (15 per cent) and Brazil (12 per cent).

Again, parsing the figures, only 2.2 per cent of global vegetable oil supply is produced and consumed by Indonesia and determined by Indonesian biodiesel policy.

But consider also that the EU is the only major biodiesel consumer that uses rapeseed for biodiesel. This means that around 3 per cent of the world’s vegetable oil supply – because of EU policies on rapeseed – is going to biodiesel.

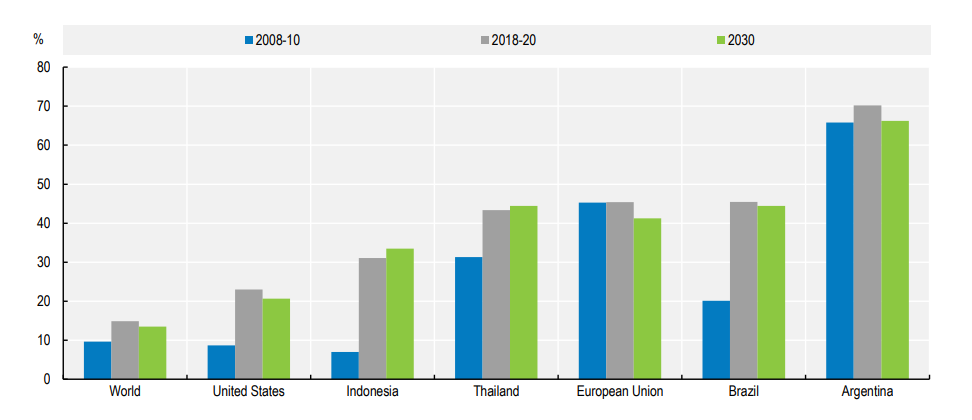

The OECD estimates that around 45 per cent of the EU’s vegetable oil consumption goes to biodiesel; this compares to 30 per cent for Indonesia.

So, is any of this the fault of Indonesian policy?

It’s worth visiting the food versus fuel debate that took place around the time of the GFC. An EU commissioned study at the time stated: “the effect of EU biofuels policies on food prices will remain very limited, with a maximum price change on the food bundle of +0.5% in Brazil and +0.14% in Europe.”

A World Bank study stated: “the effect of biofuels on food prices has not been as large as originally thought, but that the use of commodities by financial investors (the so-called ”financialization of commodities”) may have been partly responsible for the 2007/08 spike.”

And as a final note, it’s worth remembering that the push to switch away from fossil fuels for environmental and energy security reasons was pioneered by the rich world. And now wealthy countries are surprised that developing countries are following the lead?

The global spike in vegetable oil prices is a disaster; its causes are actually well-established, and have historical parallels – not to mention the ongoing effect of the war in Ukraine.

Indonesia’s export ban is not a cause; in fact, it demonstrates the level to which palm oil can and almost certainly will be an important solution to the underlying problem.